Were the Ancient Greeks more homosexual than other groups from antiquity? Were homosexuals more commonly found in Greece? Was pederasty, or man-boy-love, a common expression of gay love? And is it even fair to make broad generalizations about any group of people, whether they be Greek or gay?

This is by no means a scholarly paper. If it were, I would have done weeks of research in a university library. Rather, this is me, a history major using my blog to vent.

Last night, I had the unfortunate experience of getting into a debate with the worst kind of debater, the type of person I like to call an informed ignoramus. Unlike your typical ignoramus, the informed ignoramus possesses a kernel of knowledge about a certain subject, and using this little bit of knowledge, they often make outlandish claims that are, for lack of a better word, utter bull-crap. What was worse for me, I once considered this person my friend, someone very liberal in their views and very sensitive when it comes to matters of race and sexual orientation. He never makes broad generalizations about black people, Hispanics, Muslims, or LGBT people. Unfortunately, I am none of those things. I am Greek, and being Greek isn’t in vogue these days. You don’t see anybody on social media speaking out against Greek stereotypes, so my friend could not understand my being offended when he generalized about my ancestors.

Negative stereotypes exist for Greeks, like any other group, and it hurts just the same. People call us loud, rude, and egotistical. While this may be true for some individuals, it isn’t true for everyone I know, just as not all Asians are bad drivers and not all Irish are drunkards. But while making a “dumb Polack” joke or calling a Jewish person stingy is usually frowned upon, when it comes to the Greeks, anything goes. Make fun of us, the world says, our feelings don’t matter. Never mind that our country suffered one of the greatest, if not longest oppression in the history of the world—four hundred years—by the Ottoman Turks, or that, after our war of independence in 1821, we were left so poor that over one hundred thousand people died of starvation in a single year. Never mind the daily struggles for survival my own parents endured during their childhoods. Our recent history is swept under the rug, willfully forgotten, to make room for jokes that go back two thousand years. Most of these jokes, as you probably know, involve gay sex and pedophilia. To give you a taste, a friend of mine wrote in my senior yearbook, “How do you separate the Greek men from the boys? With a crowbar!” All I could do is use a black marker to blot out what he had written, leaving an ugly stain on a cherished childhood souvenir. Flash forward twenty years, and I am still dealing with the same kind of ignorance.

Now I have nothing against homosexuality or homosexuals. I only take offense to the notion that the Ancient Greeks were pedophiles, and somehow “more gay” than any other group. We also must not confuse, as Vladimir Putin has, sexual orientation with child abuse. As someone who has been sexually molested as a child, by a Greek relative no less, this is a sensitive subject for me.

But like all stereotypes, there is evidence to support it. Plato talked about man-boy love in the Symposium, and we know from other sources that in Athens, pubescent boys engaged in “sexual relations” with their male teachers. But how frequent and accepted was this practice? The answer is, as I often like to remind people about history, complicated.

This is a problem intrinsic to the study of history itself, and something that came up again and again when I was in graduate school. My professors consistently chastised us for making claims based on too little evidence. I’d write a paper arguing for a particular point, with a handful of references, and my professor would say to me, “Yes, but, did you read this book? And did you look at this guy? Oh, and that piece there, that’s been debunked.” The worst grade I ever got, for this very reason, wasn’t even an F. He simply wrote on the back of my paper, “You’d be crucified by any other historian!” Crucified! When I wrote my thesis on the Battle of Thermopylae, I asked my professor how many sources he wanted to see. His answer shocked me. “All of them.” And he followed that up with, “And you have it easy, in my day, we had to read every source in every language, including ancient Greek.” Shit. This is why our current Google/Wikipedia age infuriates me. YOU CANNOT SUPPLANT ACTUAL RESEARCH WITH GOOGLE.

Another problem with studying history can be thought of this way: imagine the historical record as a one thousand-piece jigsaw puzzle, but you only have about one hundred pieces, and for some parts of the world, you have almost no pieces. Now let’s extrapolate this further, using the United States as an example. Imagine you are a historian living in the year 4015, and you want to know everything you can about life in the U.S. today. So, you dig through some ruins, trying to learn what you can, and what do you come across? Religion everywhere! How many churches do we have? How many Bibles in hotel rooms? How many laws have we passed discriminating against gays based strictly on religion? With this evidence, future historians could make a strong case that America circa 2015 was utterly Puritanical. But wait, that’s just half the puzzle. After a bit more digging, archaeologists might find bookstores filled with the works of Sam Harris, Richard Dawkins, Daniel Dennet, and a number of other atheists, which may leave a lot of future historians scratching their heads in confusion.

My argument, then, when talking to my informed ignoramus friend, was that you cannot make broad generalizations about a loosely organized group of city-states, existing over two-thousand years ago, spanning centuries of time, based on the few books you’ve read. What I know about Ancient Greece, based on my studies, is that sex between a man and a boy may have been more tolerated than it is today, but that the practice was localized to a specific time, place, and social class. There is also debate regarding what these “sexual relations” actually involved. I have yet to see an image of a boy, in any museum, bent over, in the aforementioned “crowbar” position. What we do see on vase paintings is quite tame, closer to Michael Jackson-type fondling than outright sex. Conversely, there are considerable examples of heterosexual penetration on pottery, images strikingly similar to what you might find on PornHub. But again, ancient pornography is no more proof of depravity than pornographic websites prove all Americans have orgies in their bedrooms. While the Greeks did not differentiate between heterosexuals and homosexuals, we know it was socially stigmatizing for a male to be on the receiving end of sex. In times of war, male-on-male rape was often used, much like in prisons today, as a form of domination and humiliation. Given, then, the lack of “penetrative” artwork from antiquity, coupled with the stigma of male penetration, most historians believe pederasty went no further than intercrural sex, or simply, “sex between the thighs.”

Now, if we look beyond Plato, to Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, something as important to the Greek identity as the Torah is for the Jews, we find no mention of homosexuality. It has been suggested that Achilles, who fought at Troy, was involved in a gay relationship with his cousin, Patroclus, but I found no mention of this in the translation I read, and it makes no sense in the larger context of the story, considering that Achilles refuses to fight after his female lover is taken captive by King Agamemnon. No other hero is described as a homosexual, though their love interests are often central to their myths, with Odysseus traveling twenty years to return to his wife in Ithaca (while cheating on her frequently); Perseus heroically rescuing Andromache, a damsel in distress, from a giant sea monster; and Heracles, who was killed by his jealous wife after his infidelity. None of the gods engage in pederasty either, but for Apollo, and Zeus, who seduced 112 mortal women and one boy, Ganymede. In the comedy by Aristophanes, Lysistrata, the women of Athens and Sparta go on a sex strike in an effort to end the Peloponnesian War. One must wonder, if male on male sex was as rampant as some stereotypes suggest, why this would have been such a problem.

This isn’t to say that homosexuality did not exist in Ancient Greece; it certainly did, and it was probably common, but no more so than anywhere else, and it is an affront to the LGBTQ community to claim otherwise. Homosexuality is a natural occurrence, not a social aberration. If we limit sexual orientation to just one part of the world, we suggest it has nothing to do with biology. While the Hebrews strictly forbade homosexuality in Leviticus (which only goes to prove the practice existed), we know next to nothing about the Celts, the Saxons, or any other European group at the time, nor do we know anything of the habits of the people in Asia, the Russian steppes, or China. The Roman historian, Plutarch, on the other hand, asserts that the Persians engaged in pederasty with boy eunuchs, and modern historians debate how common gay relationships were in Egypt. If anything set the Greeks apart, it may be their propensity for expressing matters of eros and their tolerance for differences in sexuality.

The only thing we can say with certainty about the ancient world stems from the writings that survived, and when compared to more recent history, it is a puzzle with far too many missing pieces. For all we know, Plato and his ilk may have been the Greek equivalent of NAMBLA. Modern historian, Enid Bloch, suggests that Socrates may have suffered trauma from early sexual abuse. Are we to assume, then, that such abuse was both rampant and prevalent, in a society that gave us science, mathematics, medicine, and philosophy?

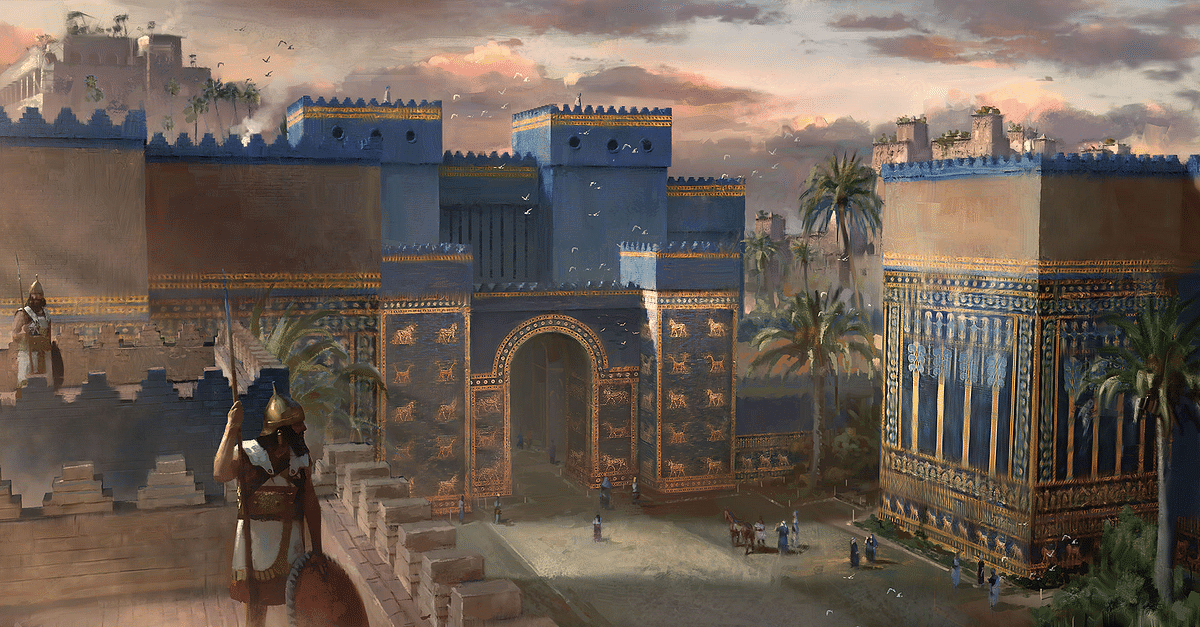

Even if we were to agree that Plato and Herodotus reflected a large part of Greek life, the writings themselves are suspect, often failing to corroborate with archaeological evidence. Herodotus states, for instance, that five million Persians (500 ten thousands) invaded Greece, which we know to be untrue, based on simple logistics; he also claimed that the city of Babylon was 10 miles by 10 miles square, also untrue. When it comes to sex and sexuality, Herodotus writes that “a woman cannot be raped,” and that there exists a country where “the men pee sitting down and the women pee standing up.” Thucydides, all the while, who is considered a much more reliable source, says almost nothing about sex or pederasty. Based on Herodotus alone, our impression of the invading Persians may reflect the film 300, but a closer look at Persian art and architecture reveals a much less violent and more sophisticated society. The same can be said of the Vikings, who were no more violent than their European neighbors, but were vilified by the writings of early Christian monks. My friend, incidentally, is Norwegian, but I would never suggest he is the descendant of rapists.

Babylon was more prosperous and less violent than Athens.

Babylon was more prosperous and less violent than Athens.

So, where does all this leave us? Were the Ancient Greeks a gay people? No more than anyone else. Were they all pedophiles? No more than anyone else. Were they overly fond of man-boy-love? No, but perhaps, at a specific time and place, were more accepting of it. Does this stereotype carry any weight? Nope. But if we must generalize, let us not say that the Greeks were more or less gay, but like much of the modern world, that they were more tolerant and enlightened.

Leave a comment