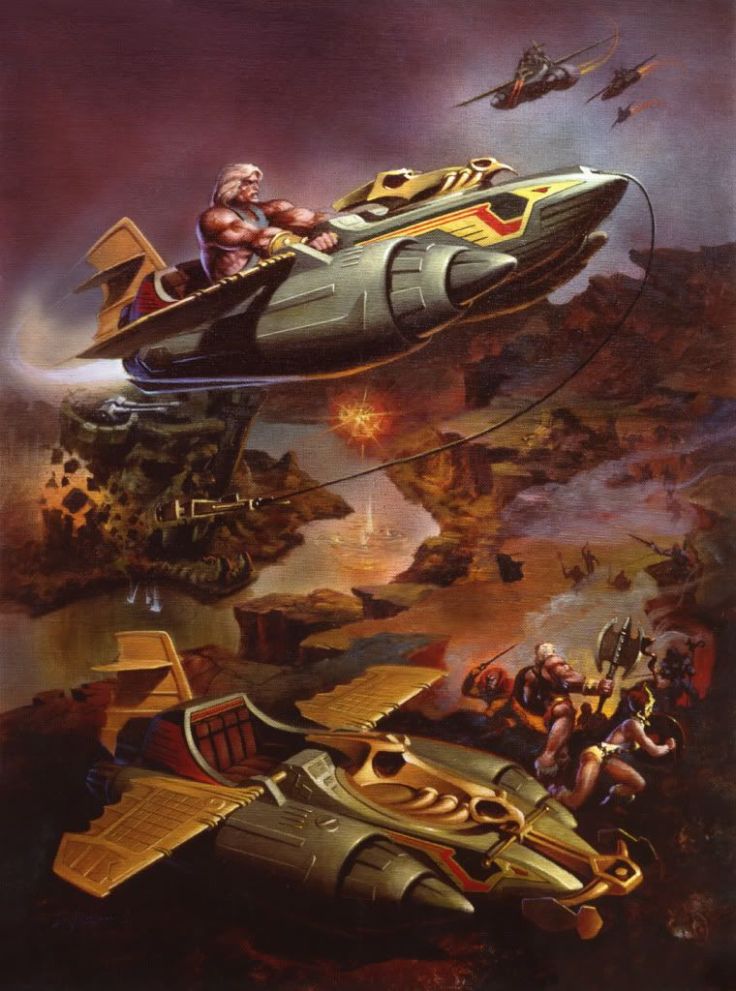

I knew the genre I would be writing in by age six, in 1981, after I’d just unboxed my first He-Man action figure. Masters of the Universe was my introduction to all things fantasy and Sci-Fi. With his furry loincloth and rippling muscles and interchangeable sword, ax, and shield, He-Man set my imagination ablaze. Even the box art, with its assortment of heroes and villains, opened my young mind to ideas that, at the time, felt almost real. It didn’t matter that He-Man was a barbarian archetype and Conan knockoff, or that his world was a mishmash of every fantasy trope from the thirties to the seventies. As far as I knew, He-Man was an original concept. But it was the mini-comic that came with the figure, Battle in the Clouds, that would determine my writing style for decades to come. At first glance, He-Man’s home-world, Eternia, appears dark and primitive. Heroes carry swords and axes and live in fanciful, skull-faced castles. There is no technology, nor modern conveniences, to speak of. But a single panel would change that perception for me, when He-Man first meets Man-at-Arms, a hero with a high-tech suit of armor. Man-at-Arms introduces He-Man to the Wind Raider. What was clear to me, early on, was how strange and out-of-place this bird-shaped vessel appeared. To He-Man’s primitive mind, the Wind Raider was magic.

|

| Fantasy meets Science Fiction in a single image. |

To this day, I find it remarkable how creators Donald F. Glut and Alfredo Alcala managed to convey, in just a single panel, a perfect marriage between fantasy and science-fiction. Countless comic book writers, movie producers, and novelists have tried to do the same, often with mixed results. Marrying Sci-Fi to fantasy is like trying to stick a round peg into a square hole, a lot more difficult than giving your hero a laser gun and a sword, which the live action Masters of the Universe movie did with disastrous results. Even the recent, much acclaimed Marvel films struggle to walk the fine line between the two genres. Despite my love for Thor, both in the comics and the original myths, I cannot help but wonder how a hammer—even Mjolnir “forged in the heart of a dying star”—can be as efficient as a gun. In Thor 2: The Dark World, Odin’s guards defend against alien elven invaders with sword and shield, while castle towers blaze with anti-aircraft artillery. It’s just one of those gaps in logic I try not to think about, or work hard to rationalize. Perhaps swords in Asgard are ceremonial?

But what makes Sci-Fi and fantasy what it is? Defining these genres determines how one can be made to complement the other, but with regards to definitions, there is much disagreement. Years back, I argued with an agent on a fiction forum over this very issue. She insisted that fantasy is any story with magic in it. But for me, it has everything to do with setting. While there are countless variations on the theme, fantasy was born out of romanticism, with an emphasis on the “mythical past that never was”. Give me a story about castles and princesses and dragons, and even without magic, it’s fantasy. Conversely, science fiction is often defined as that which deals with “science” which is usually regarded, somehow, as the opposite of magic. Some books even pit the two against each other. But this is a fundamental flaw, a literary straw-man attack on science and on what it represents. When people think Sci-Fi, they think of laser weapons and spacecraft, but these are products of technology, and do not represent the scientific method in any meaningful way.

A world without science, or more specifically, physics, cannot exist. Even cave men relied on it when building fires and carving out spears. Whether Harry Potter and his friends realize it or not, there is more physics happening at Hogwarts than magic. A wand and an incantation may levitate objects, but the force of gravity is what makes those object fall in the first place. If Harry breathes oxygen, metabolizes food, or swings the Sword of Gryffindor, the laws of physics are at work. I realize that, for most readers, physical laws are irrelevant to a fictional story; it just isn’t something one needs to think about, but I cannot shut that part of my brain off, nor would I want to. I think Arthur C. Clarke said it best, “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic,” because the secret to marrying fantasy to Sci-Fi is to recognize that there is no real difference between magic and science, that the difference in genres has everything to do with perspective. I call this Clark’s Law. In Sci-Fi, the world can be understood: a lightsaber, according to Professor Michio Kaku, is heated plasma running through a magnetic field, but in fantasy, the same sword is an enchanted blade of fire. This is why Battle in the Clouds was so brilliant all those years ago, because Masters of the Universe exists in a fantasy setting only so far as things like the Wind Raider remain ancient and mysterious and unknowable.

This is not to condemn the purely fantastical or the surreal. Not every story needs to follow logic. I adore Lovecraft, Kafka and Baum (Wizard of Oz) specifically due to their rejection of reason. But when writing from a perspective of realism, it becomes necessary to include physics into the equation (see what I did there?). There is magic in Ages of Aenya, however slight, but even then I am forced to consider the science behind it. When Emma transforms herself into a raven, I have to think long and hard about Newton’s Law of Conservation. A raven has considerably less mass than a human, so when she does transform, where does all the extra matter go? And how does she get it back when she turns back into a human? While I don’t pretend to know the answer (I chalk it up to Clarke’s law), I try to at least give science a nod, because physics must exist in a fictional universe whether an author addresses it or not. No doubt, there will remain legions of readers who hat check their brains at Chapter 1, and there will be authors who cater to those people, but for me, marrying fantasy to Sci-Fi is to acknowledge they are but two sides of the same speculative coin.

I always love when I read something you post and end up learning things abut you that even after Almost two decades of friendship I never knew. I got into MOTU at age 3 in 1986. At that point I couldn't read, and while my Mom and Grandma would read me the comics, it was the Filmation carton that was most familiar. While I wouldn't change a minute of my childhood, sometimes I hear about how magical the early comics were for you end get just a little envious.

LikeLike